How to establish an emergency

Counsel’s column

Social work regulatory boards are statutorily created and delegated with the authority to carry out the intent of the law in the interest of health, safety, and welfare of the public.

As part of this delegated statutory authority, social work boards should be delegated with the right to summarily suspend a license under certain circumstances. Summary suspension basically involves an immediate action by the board before a hearing. As an adverse action is being taken against a license without a hearing, summary/emergency suspensions are an extraordinary remedy and limited to circumstances where there is imminent harm to the public at stake. Thereafter, the licensee will be entitled to a hearing within a specified period of time, generally within 60 or 90 days. At that hearing, the status of the current summary action will be reviewed.

The ASWB Model Social Work Practice Act (model act), Article IV. Enforcement, Section 402 addresses the procedures to be undertaken and authority of the board to summarily suspend a license. Under the model act, the board may suspend a license for up to 60 days if continued practice by the social worker would create an imminent risk of harm to the public. A hearing must thereafter be scheduled within 20 days. The authority to summarily suspend a license will be set forth in statute and may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Because of the extraordinary nature of an adverse action against a license before a hearing, the scope of the immediate action against the license should be “limited” to restrictions necessary to protect the public. A summary/emergency suspension need not remove all rights to practice and must be based upon credible evidence to substantiate this action. What evidence is necessary will likely be dependent upon the facts of the situation.

Consider the following.

A male clinical social worker was providing psychotherapy services to a female client. The client informed the social worker that she had a history of anxiety and posttraumatic stress caused by a history of sexual abuse and a recent violent sexual attack. The client attended at least three therapy sessions with the social worker. During these sessions, as alleged by the client, the social worker acted flirtatiously, shared personal stories of a sexual nature, told the client she was attractive, grabbed her buttocks, and told her that he was going to miss her upon being told that she was going to find another therapist.

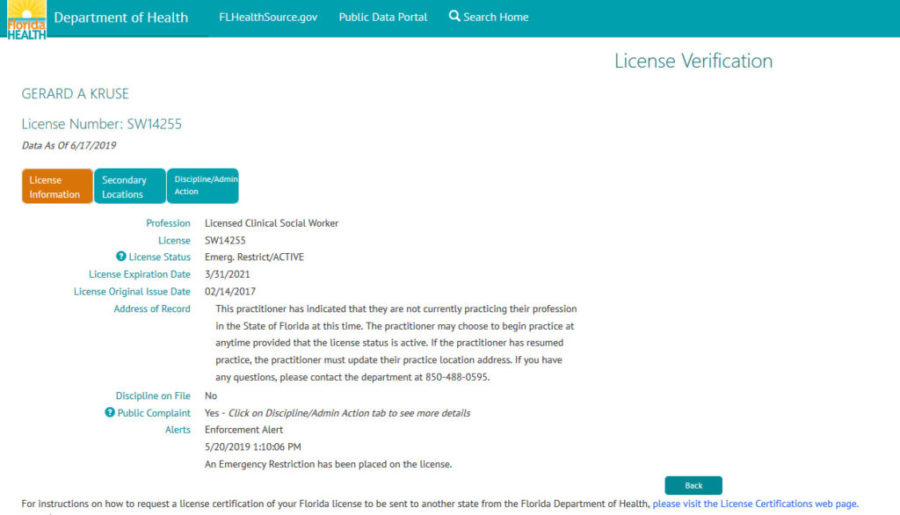

These allegations were submitted to the Florida Department of Health, which initiated immediate action. Under Florida law, the state surgeon general has the right to restrict a clinical social worker’s license “upon a finding that the clinical social worker presents an immediate, serious danger to the public health, safety, or welfare.” Further, Florida law authorizes a state agency to take emergency disciplinary action against a state licensee if the agency finds that “immediate serious danger to the public health, safety, or welfare requires emergency suspension.” Procedures followed under an emergency suspension, if undertaken, must be consistent with Florida law and the Florida and U.S. Constitutions.

The Department of Health heard testimony from the client and rendered an emergency restriction on the social worker’s license that prevented him from treating patients of the opposite sex. The social worker appealed the matter to the Florida Court of Appeals, arguing that the circumstances and the fact that this was a single act did not justify the restrictions imposed.

Under the current case, and citing previous emergency suspension cases, the court of appeals referred to the rights attached to the social worker’s license and the potential for harm caused to the client (and others) if the license remained unencumbered. The court noted the vulnerability of clients, especially under these circumstances, and referenced how social workers hold a position of power in the psychotherapist-patient relationship. The court stated that “society entrusts clinical social workers to help vulnerable people in need of guidance.”

The court distinguished previous cases cited by the social worker as to whether single acts justified immediate emergency action. In such previous cases, the accused admitted that the conduct did occur. In this case, the social worker did not admit such actions occurred. According to the court, such admissions are not an important distinction. The reliance upon the patient’s testimony turns on both the sufficiency of the facts and the credibility of the testimony. The court found that the allegations and testimony heard by the Department of Health were clearly sufficient to support the license restriction.

The court recognized the need for heightened protection of vulnerable clients/patients from sexual misconduct and noted such protection is paramount. It also held that the alleged conduct was egregious, especially under the circumstances of previous sexual abuse and assault. Finally, the court held that the restriction on the license was the least restrictive means of providing protection to the public while respecting the rights of the property interest in the license. Citing a similar case, the court noted that because such misconduct “is readily concealable…[the court] cannot fault the Department’s tailored gender-specific restriction and conclusion that ‘nothing short of the immediate restriction…will protect the public from the dangers [of continued practice].’ ”

As such, the court denied the petition filed by the social worker seeking review of the emergency order restricting his practice. The narrowly tailored order was supported by the record. Eventually, this clinical social worker will receive a hearing on the allegations and the Department of Health may, if the circumstances dictate, render a sanction against his license.

Imposing an emergency or summary suspension must respect the rights of the licensee as well as the client/patient. As referenced, a hearing is held within a reasonable period after the summary action. In this case, the alleged acts occurred in June 2017 and the appeal by the social worker of the Department of Health’s action was rendered in April 2019.

Kruse v. Department of Health, 2019 Fla. App. LEXIS 5868 (App. Ct FL 2019)